Kendrick Lamar

A Narrative Deep Dive

Kendrick Lamar's major works form a profound, evolving narrative of self-discovery. From the cinematic coming-of-age in good kid, m.A.A.d city, to the political and psychological odyssey of To Pimp a Butterfly, the internal spiritual warfare of DAMN., and finally, the raw, therapeutic confession of Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers, this is a journey through the soul of an artist and a generation.

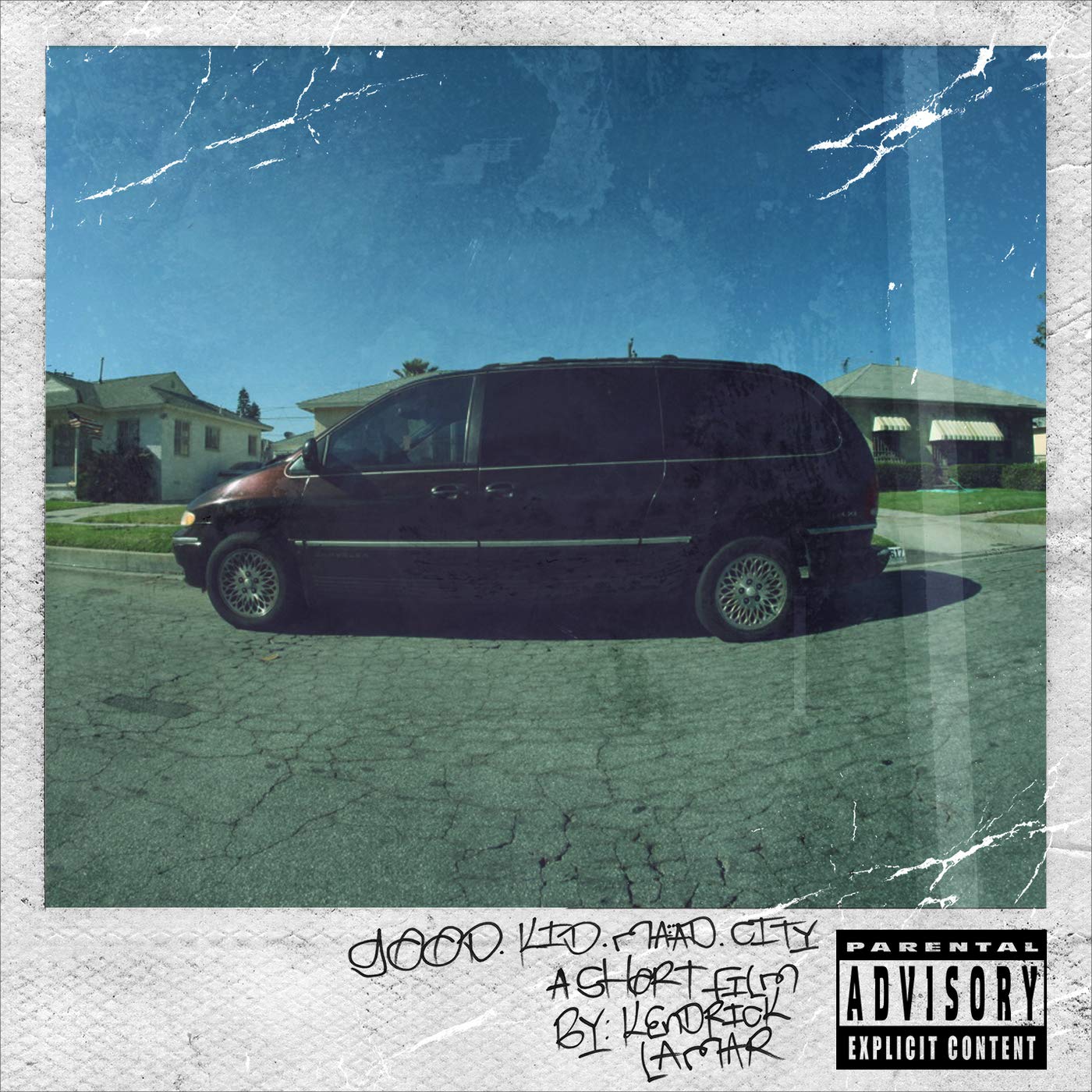

good kid, m.A.A.d city

A short film by Kendrick Lamar. The album is a cinematic narrative of a day in the life of a teenage Kendrick, navigating the temptations and dangers of Compton, and ultimately losing his innocence.

Sherane a.k.a Master Splinter’s Daughter

Narrative Role

Establishes the film's inciting incident and central conflict. The pursuit of Sherane acts as a MacGuffin, a plot device that drives the protagonist into the album's core conflicts. This journey for teenage lust is the catalyst that removes Kendrick from the 'good kid' sanctuary of his home and plunges him into the 'm.A.A.d city'.

Key Lyric Analysis

"Where you stay? She said, 'Right over there, right down the street from where your grandma stay' / That's where I seen the little light-skinned girls in little miniskirts." The specificity of location grounds the narrative in a real, mappable Compton. The reference to "light-skinned girls" introduces themes of colorism and desire that Lamar would explore more deeply on future albums.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick employs a higher-register, slightly strained vocal tone, embodying the character of his 17-year-old self. There's a palpable sense of nervous excitement and hormonal urgency, which contrasts with the more measured, reflective tone of the album's skits, highlighting the difference between his internal state and external reality.

Production Deep Dive

The production by Tha Bizness utilizes a hazy, atmospheric synth pad and a loping bassline, creating a soundscape that is simultaneously seductive and ominous. The sonic texture mirrors the Los Angeles twilight, a time of both beauty and potential danger. The inclusion of his mother's voicemails acts as a diegetic sound bridge, rooting the cinematic narrative.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The track is a case study in adolescent risk-taking behavior, driven by what psychologists call the "socioemotional system." The prefrontal cortex, responsible for impulse control, is not fully developed, leading the character to prioritize the immediate reward (meeting Sherane) over the potential long-term consequences (gang violence, parental disapproval).

Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe

Narrative Role

This track functions as the protagonist's "I Want" song, a musical theatre trope where the hero expresses their core desires. It's a moment of introspection that breaks from the linear narrative to establish the "good kid" ethos: a yearning for authenticity, spiritual fulfillment, and artistic integrity in a world of superficiality.

Key Lyric Analysis

"I'm a sinner, who's probably gonna sin again / Lord forgive me, things I don't understand." This couplet encapsulates a key theological concept in Lamar's work: a form of secular Calvinism where he acknowledges his fallen nature but still strives for grace. It's a complex portrait of faith, not as a state of purity, but as a constant struggle.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is notably relaxed and melodic, a stark contrast to the aggressive personas he adopts elsewhere. The cadence is laid-back, almost conversational, suggesting a moment of genuine, unperformed selfhood. The sigh at the beginning of the track is a non-verbal signifier of his weariness with inauthenticity.

Production Deep Dive

Sounwave's production, built around a reversed and filtered sample of "Tiden Flyer" by the Danish electronic group Boom Clap Bachelors, creates a dreamy, introspective atmosphere. The use of reversed audio contributes to a sense of looking inward, of rewinding and reflecting, which supports the song's lyrical themes.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song is an anthem for setting emotional and psychological boundaries. In an era of constant social connectivity, the plea to "not kill my vibe" is a defense mechanism against emotional vampires and the psychic toll of performative social interaction. It champions the creation of a "safe space" for one's own mental and spiritual well-being.

Backseat Freestyle

Narrative Role

This represents the performance of a constructed identity. Inside the bubble of his friends' car, Kendrick role-plays the hyper-masculine, gangster persona valued by the "m.A.A.d city." It's not who he is, but who he thinks he needs to be. This performance highlights the gap between his internal self (the "good kid") and the external pressures of his environment.

Key Lyric Analysis

"All my life I want money and power / Respect my mind or die from lead shower." This is a direct articulation of the gangster archetype's value system, prioritizing material wealth and violent enforcement of respect. The juxtaposition of "respect my mind" with "lead shower" reveals the brutal logic of this worldview, where intellectual capital is backed by lethal force.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick adopts a high-pitched, almost cartoonishly aggressive voice. This vocal choice is crucial; it signals that this is a performance, a caricature of masculinity rather than a genuine expression of it. He's playing a role, and the exaggerated voice is his costume.

Production Deep Dive

The Hit-Boy production is brutally minimalist and effective. The foundation is a distorted 808 kick drum and a simple, menacing three-note synth line. This sonic sparseness acts as a blank stage, forcing all the focus onto Kendrick's virtuosic and aggressive vocal performance. The beat doesn't coddle; it confronts.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

This track is a powerful exploration of Judith Butler's theory of performativity. Kendrick is performing a version of masculinity that is socially constructed and reinforced within his environment. It's a commentary on how identity is not just an internal state but a series of repeated, socially-coded actions and speeches.

The Art of Peer Pressure

Narrative Role

The narrative's rising action, where the stakes are elevated from joyriding to criminal activity. The song functions as a detailed, step-by-step dramatization of how group dynamics can override individual conscience. The "homies" function as a collective antagonist, pulling the protagonist deeper into the moral quagmire.

Key Lyric Analysis

"I've never been the type to bend or budge / But honestly I'm glad I'm with my homies." The first clause is a statement of his "good kid" identity, while the second is the rationalization that allows him to betray it. This internal negotiation is the core of the song's psychological drama.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is that of a seasoned narrator, calm and almost detached. This journalistic style creates a chilling effect, as he recounts dangerous and immoral acts with the clarity of a documentary voiceover. This detachment suggests a level of dissociation, a coping mechanism for the traumatic events.

Production Deep Dive

The track's genius lies in its beat switch. The first half, with its smooth, laid-back groove, sonically represents the feeling of camaraderie and belonging. The abrupt switch to a darker, more ominous beat signifies the crossing of a moral event horizon. The music tells the story as much as the lyrics do.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song is a textbook illustration of the Solomon Asch conformity experiments, which demonstrated that individuals are likely to conform to a group consensus even when it contradicts their own judgment. Kendrick becomes a case study in the power of situational forces over individual disposition.

Money Trees

Narrative Role

A moment of philosophical reflection following the adrenaline of the robbery. The track explores the central mythologies that sustain life in the "m.A.A.d city": the dream of effortless wealth ("money trees") and the shadow of sudden death. It's the "why" behind the "what" of the previous track.

Key Lyric Analysis

"It go Halle Berry or hallelujah." This iconic line is a brilliant piece of lyrical economy, encapsulating the binary outcomes of street life. It's either the pinnacle of worldly success and desire (personified by the actress) or a spiritual end (the funeral). There is no middle ground. Jay Rock's verse about the robbery provides a gritty, realistic counterpoint to Kendrick's more dreamlike contemplation.

Vocal Performance

Both Kendrick and Jay Rock adopt a hypnotic, almost weary delivery. Their cadence is relaxed but relentless, mirroring the cyclical nature of the hustle. The performance has a sense of fatalism, as if they are describing laws of nature rather than personal choices.

Production Deep Dive

The DJ Dahi production is built on a haunting, reversed sample of "Silver Soul" by the dream-pop band Beach House. This unlikely sample choice creates a hazy, dreamlike soundscape. The juxtaposition of the ethereal music with the gritty lyrics is a perfect sonic metaphor for the song's theme: the harsh reality of the streets wrapped in a beautiful, seductive dream of escape.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song explores the concept of poverty as a driver of both ambition and existential dread. The "money trees" are a symbol of economic salvation, a fantasy that provides a psychological escape from the constant stress and trauma of precarity. It connects socio-economic conditions to the mental landscape of the characters.

Poetic Justice

Narrative Role

The narrative's climax of the first act. The protagonist's initial goal (to meet Sherane) is finally reached, but the romantic fantasy is immediately shattered by the violent reality of his environment. This is the moment of "poetic justice": his pursuit of lust leads directly to a violent confrontation, a direct consequence of his earlier choices.

Key Lyric Analysis

"If I told you that a flower bloomed in a dark room, would you trust it?" This central metaphor questions the viability of love and vulnerability (the "flower") in a harsh, oppressive environment (the "dark room"). The song's narrative tragically answers the question: the flower gets trampled.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is smooth and seductive, embodying the persona of a hopeful romantic. Drake's feature, with its melodic and vulnerable tone, enhances this feeling. This softness makes the violent interruption at the end of the track (the skit) all the more jarring and effective.

Production Deep Dive

Producer Scoop DeVille masterfully samples Janet Jackson's "Any Time, Any Place," a song synonymous with 90s R&B sensuality. This sample choice creates a powerful sense of nostalgia and romantic expectation, which serves to heighten the tragic irony when that expectation is violently subverted.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The track explores how environmental trauma can inhibit the development of healthy intimate relationships. The protagonist's attempt at a normal teenage romantic encounter is thwarted by the larger systemic issues of gang violence and territorialism. It's a commentary on how external chaos can disrupt internal emotional development.

good kid

Narrative Role

This is the "dark night of the soul" for the protagonist. Having been beaten and abandoned, he is now trapped and hunted, caught in the crossfire between gangs ("Pirus and Crips") and the police. The song is a raw expression of the terror and paranoia of being a "good kid" in a world that sees him only as a threat or a target.

Key Lyric Analysis

"What am I supposed to do / When the topic is red or blue?" This rhetorical question encapsulates the central dilemma of the "good kid." He is interpellated by a system of signs (gang colors) that he does not subscribe to but cannot escape. His neutrality is impossible, and his identity is defined for him by the warring factions around him.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's vocal performance is a tour de force of rising panic. His voice becomes progressively higher-pitched and more strained with each verse, sonically representing his escalating anxiety and desperation. It's a performance of pure, unadulterated fear.

Production Deep Dive

Pharrell Williams' production is a masterclass in creating tension. The beat is driven by a nervous, twitchy bassline and punctuated by siren-like synth swells. The sonic palette is intentionally claustrophobic and paranoid, placing the listener directly inside the protagonist's frantic state of mind.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song is a powerful depiction of the psychological concept of hypervigilance, a common symptom of PTSD. The "good kid" is in a constant state of high alert, scanning his environment for threats from all sides. It's a commentary on the mental toll of living in a violent environment where one's identity is constantly being misread with potentially lethal consequences.

m.A.A.d city

Narrative Role

The album's chaotic, violent centerpiece and the full realization of the titular concept. This track plunges the listener and the protagonist into the visceral, unfiltered reality of the "m.A.A.d city." The narrative flashes back to Kendrick's first exposure to extreme violence, shattering the last vestiges of his childhood innocence.

Key Lyric Analysis

"You're lookin' at the survivor of a fatal situation." This line reframes the narrative. He's not just a participant or observer; he's a survivor. The acronym "m.A.A.d" is revealed to have dual meanings: "My Angry Adolescence Divided" and "My Angels on Angel Dust," connecting the city's violence to both psychological states and substance abuse.

Vocal Performance

The track features two distinct vocal performances. In the first half, Kendrick's delivery is aggressive, fast-paced, and relentless, mirroring the chaos of the trap beat. After the beat switch, his flow becomes more measured and narrative, in the classic G-funk storytelling tradition of his West Coast predecessors.

Production Deep Dive

The track's iconic two-part structure is its defining feature. The first beat, by Sounwave and THC, is a frantic trap banger. The abrupt switch to a smooth, bass-driven G-funk beat, produced by Terrace Martin, is a brilliant structural move. It represents a shift in time and perspective, from the immediate chaos of the present to the ingrained trauma of the past.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

This is a raw depiction of the developmental impact of witnessing violence at a young age. The song explores how such events can lead to PTSD, a normalization of violence, and a "survivor's guilt" that informs the rest of the protagonist's life. It argues that the "m.A.A.d city" is not just a place, but a psychological condition.

Swimming Pools (Drank)

Narrative Role

A narrative flashback that functions as a thematic deep dive into the "peer pressure" introduced earlier. The song deconstructs the social rituals of drinking, exposing the underlying motivations of pleasure-seeking and pain-avoidance that fuel alcohol abuse in his community.

Key Lyric Analysis

"Okay, now open your mind up and listen me, Kendrick / I am your conscience, if you do not hear me / Then you will be history, Kendrick." The song is structured as a psychomachia, a medieval literary device representing a conflict between virtues and vices for the soul of a character. Here, Kendrick's conscience battles with the allure of alcoholic oblivion.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's main vocal performance becomes progressively more slurred and intoxicated as the song progresses, a clever piece of vocal acting. This is contrasted with the clear, sober voice of his conscience, creating a palpable internal conflict.

Production Deep Dive

The T-Minus production is a Trojan horse. The hypnotic, woozy beat, with its gurgling sound effects and ethereal pads, made the song a massive club hit. However, this seductive soundscape masks a dark, cautionary tale, smuggling a message about the dangers of alcoholism into the very spaces where it is most prevalent.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The track is a sophisticated exploration of the psychology of addiction. It examines the use of alcohol as a social lubricant and a tool for emotional suppression ("kill their sorrows"). It accurately portrays the internal battle of an individual grappling with a substance use disorder, caught between the desire to fit in and the knowledge of the substance's destructive potential.

Sing About Me, I'm Dying of Thirst

Narrative Role

The album's epic, two-part climax, serving as its moral and spiritual turning point. "Sing About Me" is a moment of profound empathy, where Kendrick channels the voices of the dead and the damned. "I'm Dying of Thirst" is the subsequent spiritual crisis, leading to the protagonist's decision to seek redemption.

Key Lyric Analysis

"And when I die, I'll probably cry and say I lived a good life / 'See, you think I'm wrong, but who are you to judge?'" This line, from the perspective of the friend's brother, is a powerful challenge to the listener's moral judgment. It's a plea for understanding, not absolution, and it forces Kendrick (and the audience) to grapple with the humanity of those lost to the cycle of violence.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's performance is a masterclass in character embodiment. He subtly alters his voice and cadence for each of the three perspectives in "Sing About Me," making them feel like distinct, living individuals. In "Dying of Thirst," his delivery becomes frantic and desperate, a collective cry for help.

Production Deep Dive

The production on "Sing About Me," which samples Grant Green's "Maybe Tomorrow," is jazzy, melancholic, and spacious, creating a perfect canvas for dense, novelistic storytelling. The shift to "Dying of Thirst" brings a more frantic, percussive beat, with a repeating vocal sample that sonically represents the cyclical, desperate nature of the "thirst" for salvation.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song is a profound meditation on legacy, grief, and spiritual crisis. "Sing About Me" explores the fundamental human need to have one's story told and remembered, a form of secular immortality. "Dying of Thirst" uses the metaphor of dehydration as a symbol for spiritual emptiness and the desperate need for grace, a concept central to many recovery and religious traditions.

Real

Narrative Role

The denouement of the narrative. Following the spiritual climax, this track articulates the moral lesson that the protagonist has learned. It involves a redefinition of the term "real," moving away from the street-code definition (toughness, violence) towards a new definition rooted in self-love, responsibility, and emotional honesty.

Key Lyric Analysis

"The greatest lesson learned is that love is the only thing that's free / And real is responsibility." This couplet contains the album's central thesis. The voicemails from his father and mother ground this abstract lesson in the concrete reality of familial love, suggesting that true "realness" is found in one's closest relationships.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's vocal tone is calm, clear, and didactic. He has shed the performative personas of the rest of the album and is speaking from a place of newfound clarity and conviction. He sounds less like a rapper and more like a teacher or a recent convert sharing his testimony.

Production Deep Dive

The Terrace Martin production is bright, uplifting, and has a distinct neo-soul flavor. The warm electric piano and smooth, melodic bassline create a soundscape of peace and resolution. It's the sonic equivalent of a sunrise after a long, dark night, providing a feeling of calm and clarity.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The track is a powerful argument for a new model of masculinity. It directly confronts and rejects the toxic masculinity of the street code, replacing it with a healthier, more introspective model based on self-love and emotional intelligence. It posits that true strength lies in vulnerability and the ability to love oneself.

Compton

Narrative Role

The triumphant finale, functioning as the "credits roll" on Kendrick's "short film." Having navigated the moral and physical dangers of the city, Kendrick now celebrates it, not for its violence, but for its cultural legacy. The presence of Dr. Dre serves as a symbolic passing of the torch, anointing Kendrick as the new king of West Coast hip-hop.

Key Lyric Analysis

"So come and visit the tire smoke, the fire smoke, and yeah we might could be biased / But we all know that Compton is the city of God." This is a radical reframing. He acknowledges the city's harsh realities ("tire smoke, fire smoke") but reclaims it as a sacred space, a "city of God," because of the world-changing art and culture it has produced.

Vocal Performance

Both Kendrick and Dr. Dre deliver their verses with a palpable sense of pride and celebratory energy. Their flows are confident and charismatic. It's a victory lap, and their performances are imbued with the swagger of two generations of Compton royalty sharing the throne.

Production Deep Dive

The Just Blaze production is a masterpiece of anthemic, celebratory hip-hop. The triumphant horn fanfare, soulful vocal samples, and hard-hitting drums create a cinematic and epic soundscape. It's a fittingly grand conclusion to an album structured as a film, providing a sense of closure and triumph.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The track is an exercise in narrative therapy on a communal scale. It's about changing the story of a place, moving from a narrative of crime and poverty to one of cultural richness and resilience. This act of narrative reclamation is a powerful tool for building community pride and challenging the internalized stigma that can come from living in a marginalized area.

To Pimp a Butterfly

A dense, complex, and deeply political album exploring the black experience in America. It's a journey through depression, institutional racism, and self-hatred, ultimately culminating in a message of self-love and empowerment.

Wesley's Theory

Narrative Role

The album's explosive, disorienting overture. It introduces the central metaphor: the "butterfly" (a talented Black artist) emerging from the "cocoon" (the hood) only to be "pimped" by the predatory caterpillar of American capitalism, personified by "Uncle Sam."

Key Lyric Analysis

"Your first album deal, you spend it on a car / A gold chain, and some Jordans, you think you're a star." This line, delivered by Uncle Sam, outlines the stereotypical path of a newly successful rapper. It's a critique of conspicuous consumption as a tool of systemic economic entrapment, referencing the tax issues of Wesley Snipes as a cautionary tale.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick utilizes multiple vocal personas: a naive, high-pitched voice for the newly-signed artist; a deeper, authoritative voice for the established star; and a sinister, distorted voice for Uncle Sam. This vocal multiplicity immediately establishes the album's theatricality and internal conflict.

Production Deep Dive

Produced by Flying Lotus, the track is a chaotic masterpiece of Afrofuturism. It fuses the psychedelic funk of George Clinton (who features on the track) with free-jazz dissonance and a driving bassline from Thundercat. The sonic density and complexity mirror the overwhelming experience of being thrust into the exploitative music industry.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song is a powerful allegory for the systemic barriers faced by Black artists. The "pimping" is not just financial but psychological, creating a state of paranoia and stress. It explores how the dream of success can become a nightmare of exploitation, a common source of mental health struggles for artists in a capitalist system.

For Free? (Interlude)

Narrative Role

A frantic, confrontational interlude that directly addresses the theme of exploitation introduced in the previous track. A woman's voice berates Kendrick for not leveraging his success for material gain, which he then reframes as a metaphor for America demanding endless free labor from its Black population.

Key Lyric Analysis

"Oh America, you bad bitch, I picked cotton and made you rich / Now my dick ain't free." This is the track's stunning rhetorical pivot. The personal argument becomes a political one, linking the contemporary expectation for Black entertainers to "perform" their wealth with the historical economic exploitation of slavery. His artistic and sexual integrity becomes a symbol of reparations.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's performance is a breathless, high-speed spoken-word piece delivered in the style of the Last Poets or Gil Scott-Heron. It's a torrent of righteous anger and defiance, performed with the improvisational energy of a bebop jazz solo.

Production Deep Dive

The musical backing is pure, unadulterated free jazz, provided by Robert Glasper, Terrace Martin, and other virtuosos. The chaotic piano, racing bass, and frantic drumming create a sonic landscape of anxiety and confrontation. It's aggressively uncommercial, forcing the listener to engage with its difficult message.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The interlude connects personal psychological pressure with historical trauma. The demand to "spend money" is framed as a continuation of a historical power dynamic. Kendrick's defiant response is an act of psychological liberation, a refusal to be defined by the materialistic expectations that are a legacy of this exploitative history.

King Kunta

Narrative Role

An anthem of defiant self-assertion. After being tempted and berated, Kendrick reclaims his power. He transforms the name of the enslaved character from *Roots*, Kunta Kinte, from a symbol of victimhood into one of royalty and power. It's a moment of funk-fueled, unapologetic Black pride.

Key Lyric Analysis

"I was gonna kill a couple rappers, but they did it to themselves / Everybody's suicidal, they ain't even need my help." This is a confident dismissal of his competition. He frames their downfall not as a result of his actions, but as a consequence of their own inauthenticity. The "yams" he references ("What's the yams?") symbolize authenticity and power, drawing from Ralph Ellison's *Invisible Man*.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is pure swagger. His voice is confident, rhythmic, and filled with the bravado of a king surveying his domain. The performance is a physical act of reclamation, turning the limp of the enslaved Kunta into a confident, funky strut.

Production Deep Dive

The Sounwave and Terrace Martin production is a modern reinterpretation of classic G-funk. The track is built on a thick, undeniable bassline (a nod to DJ Quik) and a hard-hitting drum beat. The use of a talkbox and live instrumentation gives it an organic, confrontational, and infectious groove.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

This is a powerful act of psychological reframing. By taking a name associated with slavery and oppression and imbuing it with power and pride, Kendrick performs an act of radical self-love. It's a therapeutic process of turning a source of historical trauma into a source of personal strength and resilience.

Institutionalized

Narrative Role

This track explores the psychological barriers that prevent upward mobility, even when opportunities arise. Kendrick brings his friends from the hood to a world of wealth (the BET Awards), but they are unable to escape the "institutionalized" mindset of their environment, leading to a plan to commit a robbery.

Key Lyric Analysis

"And once upon a time, in a city so divine / Called West Side Compton, there stood a little nigga / He was 5-foot-something, God-bless-the-dead, he was lookin' for a purpose." This fairy-tale framing is ironic. It contrasts the idealized narrative of a hero's journey with the harsh reality of a mindset "institutionalized" by poverty and violence, which limits one's "purpose" to immediate survival and material gain.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's storytelling is calm and observational, almost like a sociologist. The highlight is the spoken-word wisdom from his grandmother ("Shit don't change 'til you get up and wash your ass"), which provides a moment of grounding, folk wisdom that contrasts sharply with the self-destructive mindset of his peers.

Production Deep Dive

The production is dreamy and disorienting, with a woozy, off-kilter groove. The psychedelic synths and Snoop Dogg's languid chorus create a surreal atmosphere, mirroring the characters' feeling of being out of place in a foreign environment. The beat itself feels "institutionalized," trapped in a repetitive, hypnotic loop.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song expands the concept of "institutionalization" from the prison system to the psychological state created by living in any oppressive environment. It's a commentary on how poverty and systemic neglect can create invisible mental prisons that are often harder to escape than physical ones, a concept explored in the work of sociologists like Loïc Wacquant.

These Walls

Narrative Role

A complex, multi-layered allegory where the "walls" represent a woman's vagina, the walls of a prison cell, and the walls of Kendrick's own conscience. The song reveals a dark secret: Kendrick has been sleeping with the baby mother of the man who killed his friend in *GKMC*, using sex as a form of protracted revenge.

Key Lyric Analysis

"If these walls could talk, they'd tell me to go deep / Yelling, 'Touch me, tease me, feel me up'." The initial verses are a seduction, but the meaning of the "walls" evolves. By the end, the walls of the prison cell are "talkin'" to his friend's killer, taunting him with the knowledge of Kendrick's actions. It's a stunning narrative reveal.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is smooth and seductive, playing the role of a lover with an undercurrent of cold calculation. His final verse, a direct address to the man in prison, is delivered with a chilling, almost sociopathic detachment, revealing the vengeful motivation behind the entire song.

Production Deep Dive

The Terrace Martin and Thundercat production is a lush, groovy funk/R&B track. The warm, inviting bassline and sensual keys create a soundscape that cleverly masks the dark, vengeful narrative. The music seduces the listener, implicating them in the act of revenge before revealing its true, ugly nature.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song is a profound exploration of how unresolved trauma and grief can manifest as destructive, harmful behavior. Kendrick's act of revenge is a maladaptive coping mechanism for the pain he experienced in *GKMC*. It's a cautionary tale about how hurt people can hurt people, perpetuating a cycle of trauma.

u

Narrative Role

The album's emotional nadir and its structural turning point. This is a raw, unflinching depiction of a complete mental and emotional breakdown. Kendrick, alone in a hotel room, confronts his deepest insecurities, self-hatred, and survivor's guilt. It is the necessary dark night of the soul before the possibility of redemption.

Key Lyric Analysis

"Loving you is complicated." This refrain, directed at himself, is a devastatingly simple and profound summary of the struggle with depression and self-loathing. The line is not an accusation from an external party, but a painful internal realization. The second half's screaming confession reveals the specific traumas fueling the breakdown, making the abstract pain concrete.

Vocal Performance

This is one of the most committed and raw vocal performances in music history. In the first half, Kendrick's voice is slurred, off-key, and drunkenly aggressive. In the second half, it dissolves into desperate, choked sobs. The performance is so realistic it is almost unbearable to listen to, shattering the fourth wall of artistic performance.

Production Deep Dive

The production is a sonic representation of a panic attack. The first half is driven by a dissonant, screaming saxophone line that mirrors a cry of psychic pain. The second half is claustrophobic and stark, with a repetitive bassline that feels like being trapped in a loop of negative self-talk. The sound of a hotel maid trying to enter the room adds a layer of narrative tension and realism.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

This track is a landmark in the depiction of Black male depression. It completely demolishes the hip-hop archetype of the stoic, emotionally invulnerable man. By performing his own breakdown with such harrowing vulnerability, Kendrick provides a powerful statement against the stigma of mental illness, illustrating the corrosive effects of survivor's guilt and the immense pressure of fame.

Alright

Narrative Role

The moment of hope and resilience that emerges from the depths of "u." It's not a denial of the pain, but a conscious choice to embrace faith and hope as an act of resistance against both personal demons and systemic oppression. It became the unofficial anthem of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Key Lyric Analysis

"Nigga, we hate po-po / Wanna kill us dead in the street for sure / Nigga, I'm at the preacher's door / My knees gettin' weak, and my gun might blow / But we gon' be alright." This sequence is crucial. It acknowledges the brutal reality of police violence and his own potential for destructive reaction, but pivots to faith ("the preacher's door") as the source of resilience.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is energetic, defiant, and uplifting. He sounds like someone pulling himself and his community out of despair. Pharrell Williams' chanted hook is a simple but powerful mantra, creating a sense of collective affirmation that is easy for a protest crowd to adopt.

Production Deep Dive

The Sounwave and Pharrell production is a brilliant synthesis of genres. It combines the hard-hitting drums of contemporary trap with the uplifting, improvisational spirit of jazz, particularly in Terrace Martin's saxophone lines. The beat itself feels like it's rising, creating a sonic metaphor for overcoming adversity.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song's power lies in its fusion of personal and political resilience. It functions as both a personal mantra for overcoming depression and a collective anthem for a social movement confronting state violence. It suggests that the fight for mental well-being and the fight for social justice are deeply intertwined, a concept central to liberation psychology.

For Sale? (Interlude)

Narrative Role

A seductive, allegorical interlude representing the temptation of selling out. Kendrick is tempted by "Lucy" (a portmanteau of Lucifer and "loose change"), who offers him all the material wealth and power of the world in exchange for his soul and artistic integrity. This is the classic Faustian bargain, updated for the hip-hop era.

Key Lyric Analysis

"My name is Lucy, I'm your dog / Motherfucker, you can live at the mall." Lucy's temptations are specific and insidious. She offers not just wealth, but a life of pure, unadulterated consumerism ("live at the mall"), a hollow substitute for genuine spiritual fulfillment. The promise to move his "mama out of Compton" makes the temptation personal and deeply understandable.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick uses a distorted, pitched-down, and sinister voice for Lucy, making the character feel both seductive and demonic. His own voice in response is hesitant and small, effectively portraying the power dynamic between a vulnerable soul and a powerful tempter.

Production Deep Dive

The production is trippy, ethereal, and hypnotic. The woozy, jazz-inflected keyboards and smooth, seductive groove create a tempting atmosphere. It's the sound of a beautiful dream that you know is about to curdle into a nightmare, perfectly capturing the deceptive nature of temptation.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

Lucy is a metaphor for the spiritually corrosive effects of unchecked capitalism and materialism. The interlude explores the mental and moral conflict that arises when artistic passion is pitted against the demands of the market. It's about the struggle to maintain a sense of self and purpose in a system that constantly tries to commodify them.

Momma

Narrative Role

A moment of profound epiphany and humility. After a symbolic journey back to the motherland (Africa), Kendrick has a conversation with a young boy that makes him realize the limits of his own knowledge. He sheds the arrogance of his success and reconnects with the fundamental truth of his origins.

Key Lyric Analysis

"I know everything, I know history and what's passin' me / I know what I know, and I know it well, not to be in a shell." The first verses are a performance of arrogance. The final verse, after his epiphany, is a complete reversal: "The day I came home, I was determined to shoot / Then you said, 'Peace to the world,' I brought a piece of it to you." He realizes true knowledge is not intellectual but spiritual.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery evolves throughout the song. He begins with a confident, almost cocky flow. In the final verse, his cadence becomes faster, more breathless, and more excited, mirroring the rush of thoughts and the sudden, overwhelming clarity of his spiritual awakening.

Production Deep Dive

The Knxwledge and Taz Arnold production is warm, soulful, and comforting. The smooth bassline and gentle keys create a feeling of homecoming. The abrupt beat switch in the final verse to a more energetic, jazzy groove sonically represents the moment of epiphany, a sudden shift in consciousness.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song speaks to the importance of cultural identity and ancestral knowledge for psychological well-being. Kendrick's journey is a metaphor for the African diaspora's search for roots. The realization that "I don't know shit" is a powerful moment of Socratic wisdom, a humbling experience that is necessary for true personal growth and the shedding of a fragile, ego-based identity.

Hood Politics

Narrative Role

A frustrated, sharp critique of the petty infighting and internal conflicts ("hood politics") that distract the Black community from the larger enemy of systemic oppression. Kendrick positions himself as an outsider who has gained a new perspective, only to be pulled back into the old conflicts.

Key Lyric Analysis

"From Compton to Congress, it's all hood politics." This is the song's brilliant, central thesis. It equates the life-or-death gang rivalries of his neighborhood with the cynical, self-serving machinations of the U.S. government. This parallel serves to demystify national politics, revealing it as just another form of tribal warfare.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is urgent, frustrated, and aggressive. He sounds like he's venting, trying to shake his community out of its self-destructive patterns. The inclusion of a real phone call at the beginning of the track grounds the song in a sense of lived reality and authenticity.

Production Deep Dive

The beat, which famously samples Sufjan Stevens' "All for Myself," is gritty, minimalist, and relentless. The driving, off-kilter drum loop and the repetitive synth line create a feeling of being stuck in a frustrating, unending cycle, which perfectly mirrors the lyrical theme.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The track is a sociological analysis of internalized oppression. It explores the "crabs in a bucket" phenomenon, where members of a marginalized group turn on each other rather than uniting to fight their common oppressor. Kendrick diagnoses this as a psychological symptom of systemic racism, a way to keep the oppressed divided and powerless.

How Much a Dollar Cost

Narrative Role

A modern-day religious parable that serves as a major test of the protagonist's character. Kendrick, at the height of his arrogance, is confronted by a homeless man who is revealed to be God in disguise. His failure to show compassion and generosity costs him his place in Heaven, a harsh lesson in humility.

Key Lyric Analysis

"He looked at me and said, 'Your potential is bittersweet' / I looked at him and said, 'Every nickel is a blank canvas, and I'm the painter'." This exchange reveals Kendrick's hubris. He sees his money as a tool for his own self-expression, while God sees it as a test of his character. The "bittersweet potential" is the tragedy of having the means to do good but choosing not to.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's performance is a masterclass in narrative acting. He portrays his own internal monologue with a palpable sense of arrogance and annoyance. The voice he uses for God is calm, steady, and filled with a weary wisdom. The contrast between these two performances makes the final revelation all the more devastating.

Production Deep Dive

The production is somber, cinematic, and deeply soulful. The mournful horns, the gospel-inflected piano, and the powerful chorus from James Fauntleroy create a mood that is both beautiful and tragic. The music functions like the score to a short, spiritual film, elevating the narrative to the level of a biblical parable.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song is a profound exploration of the psychology of wealth and its potential to corrupt the soul. It's a critique of the dehumanization that can occur when one begins to see the less fortunate not as fellow human beings but as obstacles or annoyances. It argues that a lack of empathy is a form of spiritual sickness, a theme echoed in many philosophical and religious traditions.

Complexion (A Zulu Love)

Narrative Role

A moment of healing and unity. The song is a direct and beautiful repudiation of colorism, the practice of discrimination based on skin tone that exists both outside and within the Black community. It's a crucial step in the album's journey toward collective self-love.

Key Lyric Analysis

"I'm a Zulu, I'm a Xhosa, I'm a Basotho, I'm a German / That's a joke, but my DNA says I'm a German." Rapsody's verse is a highlight, directly linking the "divide and conquer" tactics of the Willie Lynch letter, a fabricated historical document that has nonetheless been influential in Black consciousness, to the absurdity of internal prejudice. She argues that colorism is a tool of white supremacy.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is gentle, loving, and almost like a serenade. He's not preaching; he's celebrating. Rapsody's verse is confident, witty, and incisive. The combination of their energies creates a song that is both a tender call for unity and a sharp political statement.

Production Deep Dive

The production is warm, jazzy, and incredibly smooth. The gentle drums, floating Rhodes piano, and Thundercat's signature melodic bass work create a relaxed, beautiful, and loving soundscape. The music itself is an act of healing, a sonic balm for the wounds of colorism.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song is a direct therapeutic intervention against the internalized racism of colorism. This prejudice is a significant source of psychological distress, self-esteem issues, and division within the Black community. By celebrating the entire spectrum of Black skin tones, the song promotes a form of collective healing and radical self-acceptance.

The Blacker the Berry

Narrative Role

The album's furious, aggressive climax of self-confrontation. Kendrick unleashes a torrent of rage against the systemic racism that devalues his Blackness, while simultaneously turning that anger inward, accusing himself of hypocrisy for mourning the death of Trayvon Martin while having participated in the intra-community violence that kills other Black men.

Key Lyric Analysis

"So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street? / When gang-banging make me kill a nigga blacker than me? Hypocrite!" This final, shocking line is the song's conceptual core. It's a moment of devastating self-implication that forces Kendrick and the listener to confront the uncomfortable relationship between systemic oppression and internalized, self-destructive violence.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's voice is filled with a raw, almost uncontrollable rage. His delivery is percussive, aggressive, and relentless, as if he's trying to physically expel the poison of racism from his body. The contrast with the calm, patois-inflected chorus by Jamaican artist Assassin makes Kendrick's verses feel even more furious and unhinged.

Production Deep Dive

The Boi-1da and KOZ production is militant and confrontational. The booming, distorted drums and the aggressive, driving bassline create a soundscape of righteous anger and imminent conflict. It is the sonic equivalent of a war cry.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The track is a raw and painful exploration of what W.E.B. Du Bois called "double consciousness," the sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of a racist society. The song's central hypocrisy is a manifestation of this psychological split. It's a deeply uncomfortable but necessary examination of internalized racism and the complex, often contradictory, psychological state of being Black in America.

You Ain't Gotta Lie (Momma Said)

Narrative Role

A moment of calm, folksy wisdom after the storm of the previous track. Kendrick passes on the lessons his mother taught him about the value of authenticity. He critiques the performative "stunting" and posturing that is often mistaken for confidence, arguing for a quieter, more self-assured form of being.

Key Lyric Analysis

"You ain't gotta lie to kick it, my nigga / You ain't gotta try so hard." This simple, repeated refrain is the song's central piece of advice. It's a reminder that true belonging and respect do not require fabrication or performance. It's an appeal for genuine human connection over the superficiality of social posturing.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is calm, conversational, and advisory. He sounds like a wise older brother or a friend passing on a crucial life lesson. His tone is reassuring and non-judgmental, which makes the advice feel like a gentle invitation rather than a harsh command.

Production Deep Dive

The production by Lovedragon is smooth, groovy, and laid-back. The relaxed bassline, gentle keys, and soulful background vocals create a "sitting on the front porch" atmosphere. The music is as comfortable, unpretentious, and self-assured as the message it promotes.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song directly addresses the social anxiety and insecurity that fuel performative behavior. The psychological need to "lie to kick it" stems from a deep-seated fear of not being accepted for one's authentic self. The song promotes a form of mental health rooted in radical self-acceptance and the courage to be vulnerable and genuine.

i

Narrative Role

The album's joyful, therapeutic climax. "i" is a radical declaration of self-love, serving as the direct antidote to the suicidal ideation of "u." The album version, a "live" performance, breaks down into a spoken-word piece where Kendrick stops a fight, putting the song's message of love and unity into direct, real-world action.

Key Lyric Analysis

"And I love myself!" (screamed with raw, unadulterated passion). This is the most direct and powerful statement on the album. After a long journey through self-hatred and depression, this is a radical, political, and life-affirming declaration of self-worth. The spoken-word section reclaims the etymology of the n-word, linking individual self-love to a broader, communal love.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's performance is pure, infectious joy. He's singing, rapping, and shouting with an energy that is both celebratory and defiant. The "live" performance on the album version, where his voice cracks with exasperation as he breaks up the fight, adds a layer of raw, messy, real-world urgency to the song's idealistic message.

Production Deep Dive

The production is built around a prominent, joyful sample of "That Lady" by The Isley Brothers, immediately giving the track a classic, celebratory funk feel. The use of a live band on the album version makes the song feel organic, communal, and spontaneous, as if it's a celebration happening in real time.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

This is one of the most important mental health anthems in modern music. It frames self-love not as a narcissistic or selfish act, but as a radical, political, and life-saving act of resistance, especially for Black people living in a society that systematically devalues them. The speech at the end connects individual mental health ("loving yourself") to the collective mental health of the entire community.

Mortal Man

Narrative Role

The album's epic, meta-textual conclusion. Kendrick completes the poem he has been reciting in fragments throughout the album, revealing that he has been reading it to his hero, the late Tupac Shakur. The track culminates in a simulated conversation with Tupac (using archival interview audio), where Kendrick seeks guidance on how to use his platform for revolution.

Key Lyric Analysis

"When shit hit the fan, is you still a fan?" This question, which frames the entire song, is a direct challenge to the listener. It's a test of loyalty and a prescient acknowledgment of the difficult, controversial path he intends to walk as an artist. He is asking if his audience is prepared for the responsibilities that come with his art.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is serious, questioning, and deeply reverent. He sounds like a student seeking wisdom from a master. During the "interview" with Tupac, his voice is filled with a mix of awe, hope, and a palpable anxiety about the weight of the legacy he is inheriting.

Production Deep Dive

The production is cinematic and somber, with sweeping strings and a mournful saxophone line. The beat is understated, allowing the focus to remain on Kendrick's dense, philosophical lyrics. The technical skill involved in seamlessly editing the Tupac interview audio to create the illusion of a real-time conversation is a stunning piece of conceptual production.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The track explores the immense psychological burden of leadership and influence, a condition that could be termed "prophet's anxiety." Kendrick's search for guidance from a fallen icon speaks to the profound loneliness and pressure of being the "voice of a generation." The final image of the caterpillar and the butterfly is a sobering allegory for how even the most revolutionary artists can be "pimped" and consumed by the very systems they seek to change.

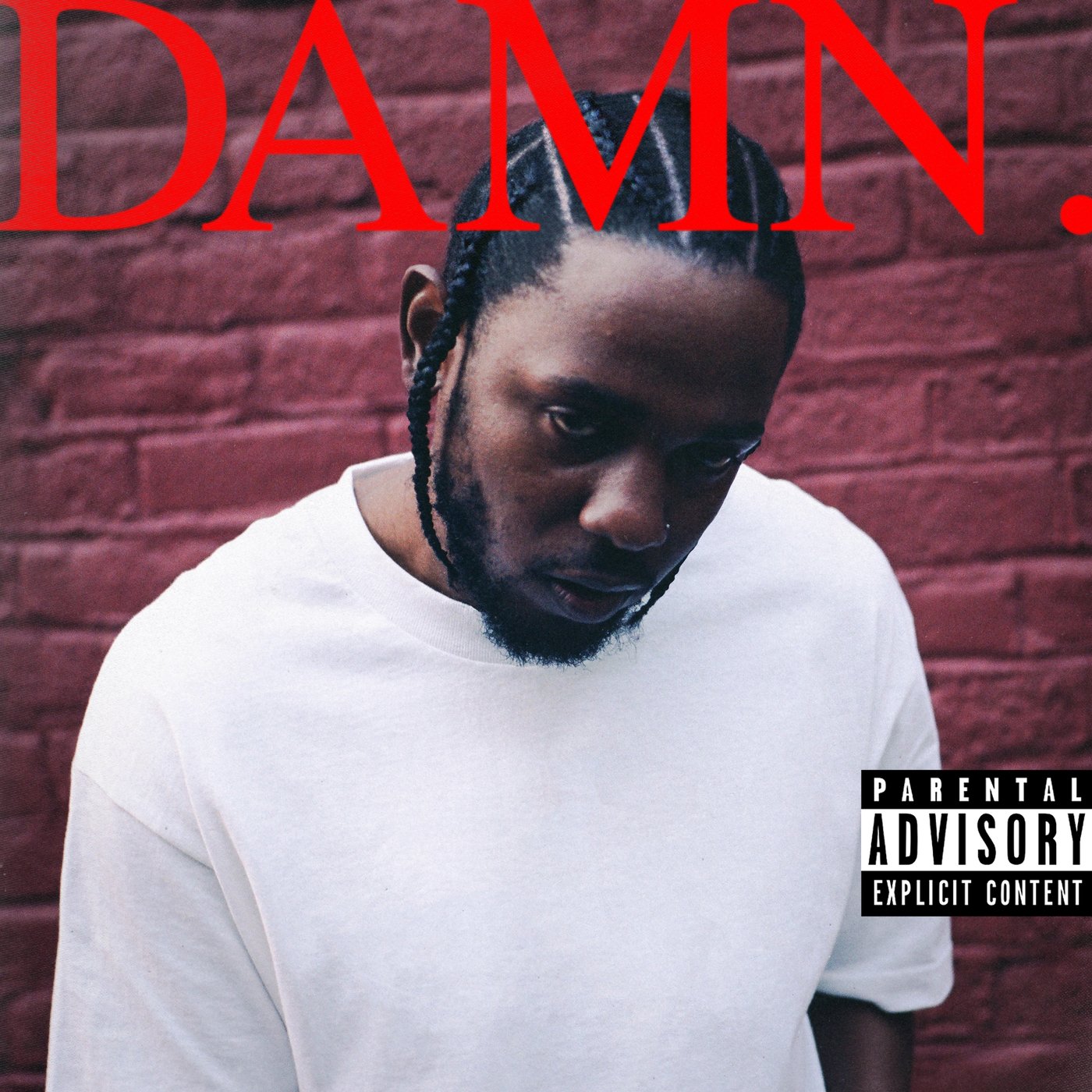

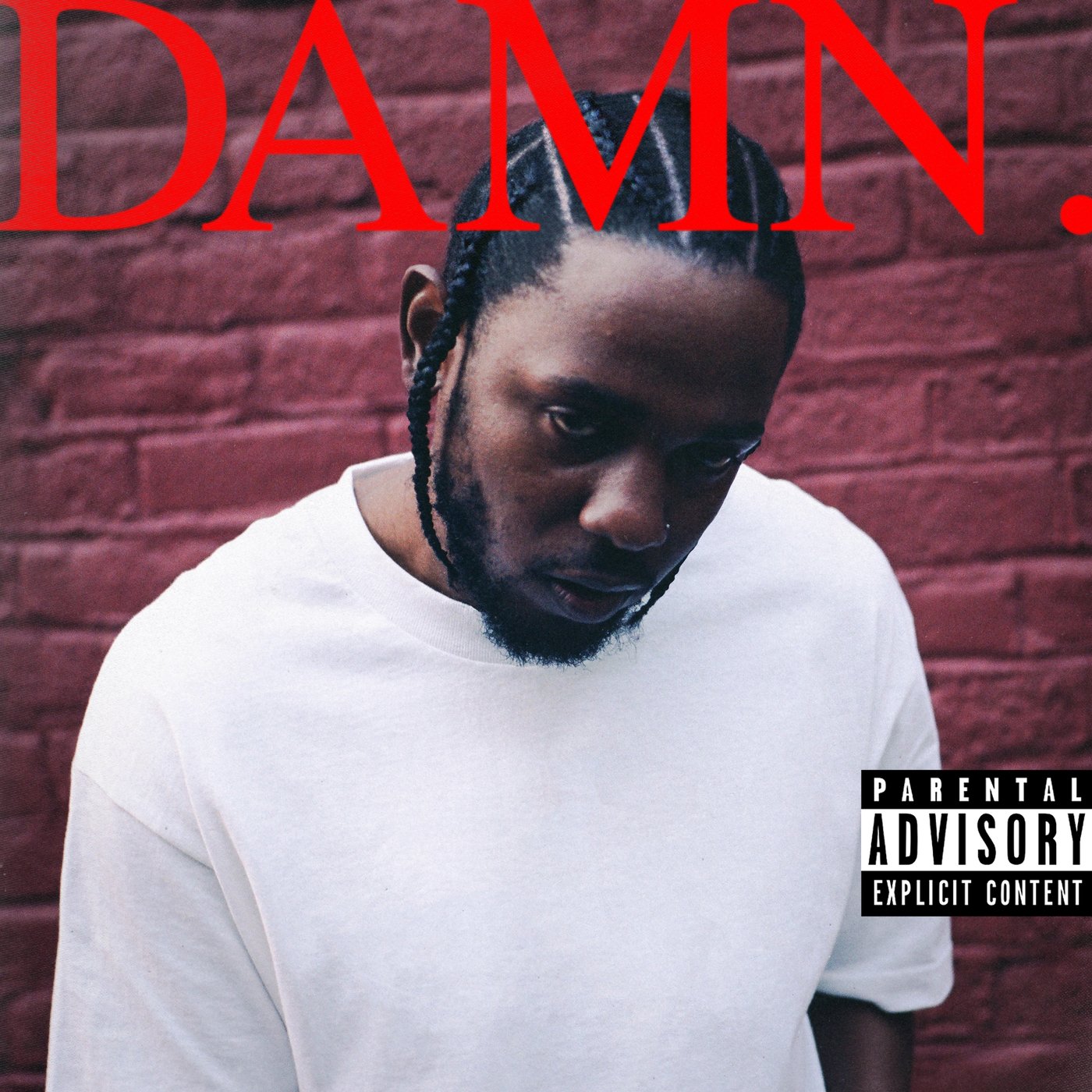

DAMN.

A Pulitzer Prize-winning exploration of duality. The album can be played forwards or backwards, telling two different stories about "wickedness" and "weakness," fate, religion, and Kendrick's place in a chaotic world.

BLOOD.

Narrative Role

The album's opening parable, which establishes the central thematic conflict. Kendrick, attempting an act of kindness, is killed by the blind woman he tries to help. This event poses the question that frames the entire album: Was his downfall a result of his own "wickedness" or his inherent "weakness"? The narrative is immediately established as a theological investigation.

Key Lyric Analysis

"'You have lost... your life.' *Gunshot*". The abruptness of the violence following an act of charity introduces the album's themes of fate, cosmic irony, and the chaotic nature of morality. The subsequent sample of Fox News anchors criticizing his lyrics immediately politicizes this death, linking his personal fate to a national conversation.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is calm, measured, and narrative, like the voiceover in a film noir. This detached tone makes the sudden violence of the gunshot profoundly shocking, creating a powerful contrast between his calm intentions and the chaotic outcome.

Production Deep Dive

The production is sparse and cinematic, featuring melancholic strings and no drums. This creates a sense of foreboding and allows the focus to be entirely on the narrative. The abrupt cut from the music to the Fox News sample is a jarring editorial choice that functions as the album's true inciting incident.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The track explores a state of existential anxiety, where the world seems governed by chaos rather than moral logic. The idea that a good deed can be punished with death speaks to a feeling of cosmic injustice and paranoia, a sense that the universe itself is hostile and unpredictable.

DNA.

Narrative Role

A defiant declaration of identity in the face of the criticism introduced in the previous track. Kendrick argues that his essence—his talent, his trauma, his heritage—is not a choice but an immutable fact encoded in his very DNA. It's an assertion of biological and spiritual determinism.

Key Lyric Analysis

"I got loyalty, got royalty inside my DNA." This is a direct claim to a noble lineage, both cultural (hip-hop royalty) and spiritual (as a descendant of the Israelites, a theme explored later). The list of contrasting traits ("power, poison, pain, and joy") establishes the theme of duality as an essential part of his identity.

Vocal Performance

This is a technical marvel of a vocal performance. Kendrick's flow is aggressive, percussive, and breathtakingly complex. After the beat switch, his delivery becomes even more frantic and breathless, a virtuosic display of lyrical athleticism that sonically embodies the power he claims to possess.

Production Deep Dive

The Mike WiLL Made-It beat is iconic for its aggression and its brilliant structural turn. The first half is a hard-hitting trap banger. The beat switch, ingeniously triggered by a sample of Fox News anchor Geraldo Rivera criticizing his lyrics, launches the track into an even more chaotic and aggressive second act.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song is a powerful statement on the concept of generational inheritance, both of trauma and resilience. It can be read as an exploration of epigenetics, the idea that the experiences of one's ancestors can affect one's own genetic expression. It's an anthem of defiance against racist narratives, reframing Black identity as a source of immense, complex power.

YAH.

Narrative Role

The comedown after the adrenaline of "DNA." This track finds Kendrick in a more contemplative and paranoid state, reflecting on the pressures of fame, his family, and his controversial religious beliefs (specifically, his identification with the Black Hebrew Israelites, who use "Yah" for God).

Key Lyric Analysis

"I'm an Israelite, don't call me Black no more / That word is only a color, it ain't facts no more." This is a direct statement of his controversial theological position, which runs as a subtext throughout the album. He is rejecting a socially constructed racial identity in favor of what he believes to be a more profound, spiritual one.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is hazy, laid-back, and almost mumbled, a complete sonic departure from the previous track. He sounds weary and introspective, as if retreating into his own thoughts to process the chaos of his public life.

Production Deep Dive

The Sounwave and DJ Dahi production is woozy and psychedelic. The loping bassline, minimalist drums, and reversed vocal samples create a hazy, introspective atmosphere. It's the sonic equivalent of a smoke-filled, paranoid mind, perfect for the song's themes of conspiracy and exhaustion.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The track is a perfect depiction of the mental exhaustion and information overload of modern fame. He is buffeted by news cycles ("Fox News wanna use my name for percentage"), family obligations, and complex spiritual questions. It captures the psychological state of needing to withdraw from the world to find a moment of clarity.

ELEMENT.

Narrative Role

An assertion of dominance and artistic commitment. Kendrick contrasts his willingness to "die for this shit" with the perceived superficiality of his rivals. He embraces the aggressive, competitive aspect of his persona, framing his success as a result of unparalleled dedication and sacrifice.

Key Lyric Analysis

"Mr. One through Five, that's the only logic / Fake my death, go to Cuba, that's the only option." The "one through five" refers to his consistent ranking as one of the top rappers alive. The reference to faking his death and fleeing to Cuba is a nod to Tupac conspiracy theories, positioning himself as an artist of similar legendary status and mystique.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is confident and melodic, but with a sharp, aggressive edge. He's not shouting; he's stating his superiority as a matter of fact. The sung hook ("If I gotta slap a pussy-ass nigga, I'ma make it look sexy") is a brilliant and disturbing fusion of violence and style.

Production Deep Dive

The piano-driven beat, produced by Sounwave, James Blake, and Ricci Riera, is a study in contrasts. The beautiful, melancholic piano melody is juxtaposed with hard-hitting, modern trap drums. This production choice perfectly mirrors the song's lyrical theme: the brutal reality of the rap game wrapped in the beautiful artistry of his music.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song explores the psychology of extreme ambition and the "win at all costs" mentality. The repeated references to violence and sacrifice can be read as a commentary on the often-unhealthy levels of obsession and competitive drive that are glorified in capitalist culture and the entertainment industry.

FEEL.

Narrative Role

A raw, unfiltered stream-of-consciousness dive into the depths of Kendrick's depression and isolation. This is the "weakness" side of the album's central duality, a direct expression of the profound loneliness and paranoia that success has brought him.

Key Lyric Analysis

"I feel like a chip on my shoulders / I feel like I'm losin' my focus / I feel like I'm losin' my patience / I feel like my thoughts in the basement." The anaphora of "I feel like" turns the song into a relentless inventory of his anxieties. It's a raw data-dump from his psyche, with no narrative filter, mirroring the racing, intrusive thoughts of an anxiety attack.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's voice is raw, desperate, and relentless. His flow tumbles over itself, as if he can't get the words out fast enough to keep up with his racing mind. You can hear the genuine pain and strain in his delivery, making it one of his most emotionally exposed performances.

Production Deep Dive

The Sounwave production is minimalist and claustrophobic. The beat consists of a simple, repetitive drum pattern and a murky, distorted bassline. The almost complete lack of melody creates a feeling of being trapped in a dark, empty room with only your own negative thoughts for company.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

This is a powerful and accurate depiction of high-functioning depression. Despite his immense success, Kendrick feels completely isolated ("Ain't nobody prayin' for me"). The song gives voice to the profound loneliness of struggling with mental illness while maintaining a successful public facade, a common experience that is rarely articulated with such honesty.

LOYALTY.

Narrative Role

A thematic exploration of trust and allegiance in a world corrupted by fame and money. Featuring Rihanna, the track serves as a more commercially accessible moment that nonetheless continues the album's central theological and ethical investigation. It asks what, or who, we are truly loyal to.

Key Lyric Analysis

"Tell me who you loyal to / Is it money? Is it fame? Is it weed? Is it drink? / Is it comin' down with the loud pipes and the rain?" Kendrick expands the concept of loyalty beyond simple interpersonal fidelity. He presents a list of false idols—money, fame, hedonism—and forces himself and the listener to question the true foundation of their commitments.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is smooth and melodic, a perfect complement to the song's radio-friendly vibe. Rihanna's vocals add a layer of cool, confident sensuality. Their vocal chemistry transforms the song's central question into a genuine, intimate conversation between two equals navigating the treacherous waters of fame.

Production Deep Dive

The production is a clever piece of pop craftsmanship. It is built around a reversed and manipulated sample of the intro to Bruno Mars' "24K Magic," transforming a celebratory anthem into a hypnotic, questioning loop. The modern trap drums ground the track, creating a product that is both sonically interesting and commercially viable.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song explores the anxiety of trust in a hyper-transactional world. The constant questioning of loyalty speaks to a deep-seated fear of betrayal, an anxiety that is often magnified by the pressures of wealth and public life. It's about the fundamental human search for genuine, unconditional connection in a world where relationships often feel conditional.

PRIDE.

Narrative Role

A psychedelic, introspective exploration of one of the seven deadly sins. Kendrick wrestles with the conflict between his spiritual aspiration for humility and the ego-inflating reality of his success. He acknowledges that pride is a "poison" and a fundamental obstacle on his path to grace.

Key Lyric Analysis

"See, in a perfect world, I'll choose faith over riches / I'll choose work over bitches / I'll make schools out of prisons / I'll take all the religions and put 'em all in one service." He lays out a utopian vision of his own virtue, but the dreamy, detached tone of the song suggests that he knows this "perfect world" is an illusion. It highlights the painful gap between his ideal self and his flawed, human reality.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's main vocal is pitched up and drenched in reverb, giving it a detached, ethereal quality, as if it's the voice of his disembodied conscience. This is contrasted with the lower-pitched, more grounded vocal that closes the track, representing a reluctant return to his flawed, earthly self.

Production Deep Dive

The hazy, psychedelic production, led by a languid guitar line from guest artist Steve Lacy, is a significant sonic departure for the album. The slow tempo and dreamy textures create a contemplative and introspective mood, perfectly suited for a song about a deep, internal spiritual crisis.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song is a deep psychological and spiritual dive into the nature of ego. While pride is often framed as a positive trait (e.g., "pride in one's work"), here it is explored in its classical sense as a deadly sin—a source of isolation, delusion, and spiritual sickness. The song is about the difficult, internal work of cultivating genuine humility in a world that constantly rewards ego.

HUMBLE.

Narrative Role

The aggressive, bombastic counterpoint to the introspection of "PRIDE." This track represents the "wickedness" side of the album's duality. It's a confident, ego-driven assertion of dominance, where Kendrick commands his rivals (and, paradoxically, himself) to be humble in the face of his greatness.

Key Lyric Analysis

"I'm so fuckin' sick and tired of the Photoshop / Show me somethin' natural like afro on Richard Pryor / Show me somethin' natural like ass with some stretch marks." This couplet, a critique of unrealistic beauty standards, was widely debated. It serves as a moment of "realness" in an otherwise braggadocious anthem, but it's a "realness" asserted from a position of immense power and authority, complicating its message.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is staccato, aggressive, and incredibly confident. It's not a suggestion; it's a command. The sheer energy and conviction of the performance made it an instant global anthem, a testament to the power of his vocal authority.

Production Deep Dive

The Mike WiLL Made-It beat is a masterclass in aggressive minimalism. It is driven by a hard, distorted piano loop and booming 808 bass. The stark simplicity of the beat is its greatest strength, providing the perfect, confrontational platform for Kendrick's commanding vocal performance.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song embodies a central paradox of ego and self-esteem. The act of demanding humility from others is, itself, an act of supreme pride. This internal contradiction reflects a real psychological struggle: how does one maintain a healthy sense of self-confidence without tipping over into destructive arrogance? The song doesn't resolve this conflict; it performs it.

LUST.

Narrative Role

A hypnotic, repetitive track that depicts the monotonous, soul-crushing cycle of hedonism. The song portrays the life of a successful artist on the road not as a glamorous fantasy, but as a boring, mechanical routine of empty pleasures, revealing the spiritual emptiness that can accompany material success.

Key Lyric Analysis

"Wake up, get a drink, wake up, get a drink / Wake up, smoke a blunt, wake up, get a drink / Wake up, grab a gun, wake up, leave the house." The mundane, repetitive structure of the lyrics mirrors the cyclical, empty nature of the lifestyle he's describing. The sudden intrusion of "grab a gun" suggests the underlying violence and paranoia that this numb existence cannot fully suppress.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's vocal delivery is intentionally monotonous, detached, and almost robotic. He sounds bored and numb, a crucial performance choice that drains all the glamour from the rockstar lifestyle and exposes its underlying spiritual desolation.

Production Deep Dive

The production by DJ Dahi and Sounwave is hypnotic and disorienting. The lurching, repetitive groove and the use of reversed audio elements create a woozy, cyclical feeling. The beat feels like being stuck on a broken fairground ride, a sonic metaphor for the inescapable, nauseating cycle of lust.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song is a powerful depiction of anhedonia, the clinical inability to feel pleasure, which is a core symptom of depression. It explores how the relentless pursuit of hedonistic pleasure, often glorified in celebrity culture, can paradoxically lead to a state of profound numbness and spiritual death. It's a cautionary tale about the mental health consequences of a hollow, materialistic lifestyle.

LOVE.

Narrative Role

A moment of tender, vulnerable sincerity that serves as a stark contrast to the cynical hedonism of "LUST." Kendrick seeks reassurance of unconditional love, a stable anchor in the chaotic, transactional world of fame. It's a plea for a love that is not dependent on his success or status.

Key Lyric Analysis

"If I didn't have a dollar, would you still love me? / Keep it a whole one hundred, I'm tryna be your everything." This simple, direct question is the emotional core of the song. In an album obsessed with the corrupting influence of wealth, this is a search for something real and transcendent. The phrase "keep it a whole one hundred" grounds this romantic plea in the language of street authenticity.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's performance is soft, melodic, and emotionally vulnerable. He sings more than he raps, and his tone is filled with a genuine sense of tenderness and anxious longing. It's a rare moment of unguarded romanticism in his discography.

Production Deep Dive

The warm, synth-pop production is bright, uplifting, and accessible. The gentle keys, the simple, effective drum pattern, and Zacari's smooth, memorable hook create a feeling of warmth and intimacy. It's the sonic equivalent of a safe harbor from the album's darker, more turbulent themes.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song explores the fundamental human need for secure attachment as a cornerstone of mental well-being. The anxiety expressed in the song—the fear of abandonment if success were to fade—is a deeply human one. It highlights how a stable, loving relationship can function as a powerful psychological anchor against the existential anxieties of a precarious and often superficial world.

XXX.

Narrative Role

A chaotic, three-act morality play that explores the hypocrisy of violence in America. When a friend calls Kendrick for spiritual guidance after his son is killed, Kendrick, the thoughtful prophet, can only offer the violent logic of the streets. This personal hypocrisy is then scaled up to a national level, equating street violence with American foreign policy.

Key Lyric Analysis

"I can't sugarcoat the answer for you, this is how I feel / If somebody kill my son, that mean somebody gettin' killed." This is a moment of shocking, brutal honesty. Kendrick admits that in the face of profound grief, his sophisticated moral and political philosophy collapses, and he reverts to a primal, retaliatory instinct. This reveals the fragility of his own "prophet" persona.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's vocal performance shifts dramatically with the beat. He starts calm and narrative, becomes aggressive and violent, and then transitions to a frantic, breathless critique of America. The soaring, anthemic vocals from U2's Bono in the final section add a layer of epic, tragic irony to the song's chaotic message.

Production Deep Dive

The production is a jarring, three-act structure. It begins with a minimalist beat, explodes into a chaotic trap banger complete with police sirens, and then resolves into a more traditional, soulful boom-bap rhythm for the final act. The abrupt, disorienting beat switches mirror the chaotic and contradictory nature of American violence.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song is a powerful statement on the psychological phenomenon of cognitive dissonance. It explores how individuals and nations can hold contradictory beliefs about violence, condemning it in one context (e.g., on the street) while celebrating it in another (e.g., in war). It argues that the "gangster" mentality is not an aberration but a microcosm of the national psyche.

FEAR.

Narrative Role

The album's lyrical and conceptual centerpiece, a seven-minute psycho-autobiography that traces the evolution of Kendrick's fear. He chronicles his anxieties at three distinct life stages: the fear of his mother's discipline at age 7, the fear of dying in the streets at 17, and the fear of losing his success and sanity at 27. It's the key to understanding the album's entire psychological landscape.

Key Lyric Analysis

"At 27, my biggest fear was losin' it all / Scared to spend money, had me sleepin' from hall to hall / Scared to go back to Section 8 with my momma stressin'." This section provides a raw, honest look at the anxieties of success. It reveals that wealth doesn't eliminate fear but simply changes its object, from fear of physical death to fear of social and economic death.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's performance is a stunning feat of vocal acting. His voice evolves with the narrative: he sounds small and childlike in the first verse, more confident but still anxious in the second, and weary and paranoid in the third. It's a vocal performance that charts a lifetime of anxiety.

Production Deep Dive

The Alchemist's production is a masterclass in subtlety. The beat is a slow, mournful, and soulful loop that gives Kendrick's dense, novelistic lyrics ample space to breathe. The reversed voicemail from his cousin Carl at the end provides the theological framework for these fears, linking them to the curse described in Deuteronomy.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

This is one of the most profound and detailed explorations of anxiety in modern music. It illustrates how fear is not a static emotion but a constant, evolving presence throughout a life, shaped by one's age, environment, and circumstances. By providing a longitudinal study of his own anxiety, Kendrick creates a powerful and deeply relatable narrative of a mind shaped by fear.

GOD.

Narrative Role

A triumphant, almost arrogant celebration of success that represents the opposite emotional pole from "FEAR." This track embodies the "wickedness" of pride and ego. After exploring the depths of his anxiety, Kendrick swings to the other extreme, reveling in the intoxicating, god-like feeling of being at the pinnacle of his profession.

Key Lyric Analysis

"This what God feel like / Laughin' to the bank like, 'A-ha!'" This repeated line is a moment of pure, unadulterated hubris. The juxtaposition of a divine feeling with the profane act of "laughing to the bank" reveals the source of this "godliness": not spiritual enlightenment, but immense material success. It's a dangerous and seductive state of mind.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's vocal performance is melodic, triumphant, and carefree. He uses a catchy, sing-song, trap-influenced flow that is incredibly confident and charismatic. He sounds completely untouchable, floating on the beat with the effortless grace of someone who believes they are omnipotent.

Production Deep Dive

The production is a bright, synth-heavy, trap-pop banger. It's one of the most commercially accessible tracks on the album, with a celebratory and uplifting feel that sonically represents the intoxicating feeling of god-like success that Kendrick is describing.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song can be interpreted as a stunningly accurate depiction of a manic or hypomanic episode, the emotional peak that often follows or precedes a depressive state in bipolar disorder. The dramatic swing from the deep, paranoid anxiety of "FEAR." to the supreme, almost delusional, arrogance of "GOD." mirrors the emotional volatility of a mood disorder, adding another layer of psychological complexity to the album.

DUCKWORTH.

Narrative Role

The album's stunning, conceptual conclusion, a true story that retroactively explains the entire project's obsession with fate, chance, and divine intervention. Kendrick tells the story of a fateful encounter between his father, "Ducky," and his future record label boss, Anthony "Top Dawg" Tiffith, an encounter that could have ended in murder. A simple act of kindness alters their destinies and makes Kendrick's own life possible.

Key Lyric Analysis

"Whoever thought the greatest rapper would be from coincidence? / Because if Anthony killed Ducky, Top Dawg could be servin' life / While I grew up without a father and die in a gunfight." This is the breathtaking revelation. Kendrick lays out the alternate reality, demonstrating how a single, small decision—a choice for kindness over strict business—radically altered the course of his life and, by extension, modern music history.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick is in his master storyteller mode. His delivery is clear, precise, and filled with a sense of gravity and wonder. He's not just rapping; he's delivering a sermon on the intricate, unpredictable nature of fate and consequence. His tone conveys the immense weight and improbability of the story he's telling.

Production Deep Dive

The 9th Wonder production is a tour de force of soul sampling, flipping between three distinct beats to score the different acts of this narrative triptych. The warm, soulful production gives the track a nostalgic, almost mythological feel, as if it's a folk tale being passed down through generations. The final sound of the entire album rewinding is a brilliant piece of conceptual production, reinforcing the song's central theme.

Societal/Mental Health Connection

The song is a profound meditation on the "butterfly effect" and the philosophical debate between determinism and free will. The story suggests that our lives are a complex tapestry woven from chance, small choices, and grace. This perspective can be a powerful antidote to the anxiety of modern life, replacing a narrative of pure, stressful individualism with one of interconnectedness, wonder, and gratitude for the sheer improbability of existence.

Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers

A raw, theatrical, and deeply personal double album framed as a therapy session. Kendrick dismantles his own myth, confronting generational trauma, infidelity, and the contradictions of being a saviour figure.

United In Grief

Narrative Role

The album's chaotic overture, framed as a dramatic monologue in a therapy session. Kendrick confesses to "1855 days" of creative stasis and emotional turmoil since his last album, revealing his attempts to cope with unprocessed grief through materialism and lust. It immediately establishes the album's therapeutic framework.

Key Lyric Analysis

"I grieve different." This refrain is the key to the song and the album. It reframes his past actions—the conspicuous consumption, the infidelity—not as moral failures, but as maladaptive coping mechanisms for grief. It's a radical act of re-contextualization through a therapeutic lens.

Vocal Performance

Kendrick's delivery is frantic, percussive, and breathless, mirroring the chaotic internal state of someone having a long-overdue emotional breakthrough. The performance is intentionally overwhelming, simulating the feeling of a dam of repressed trauma finally breaking.

Production Deep Dive